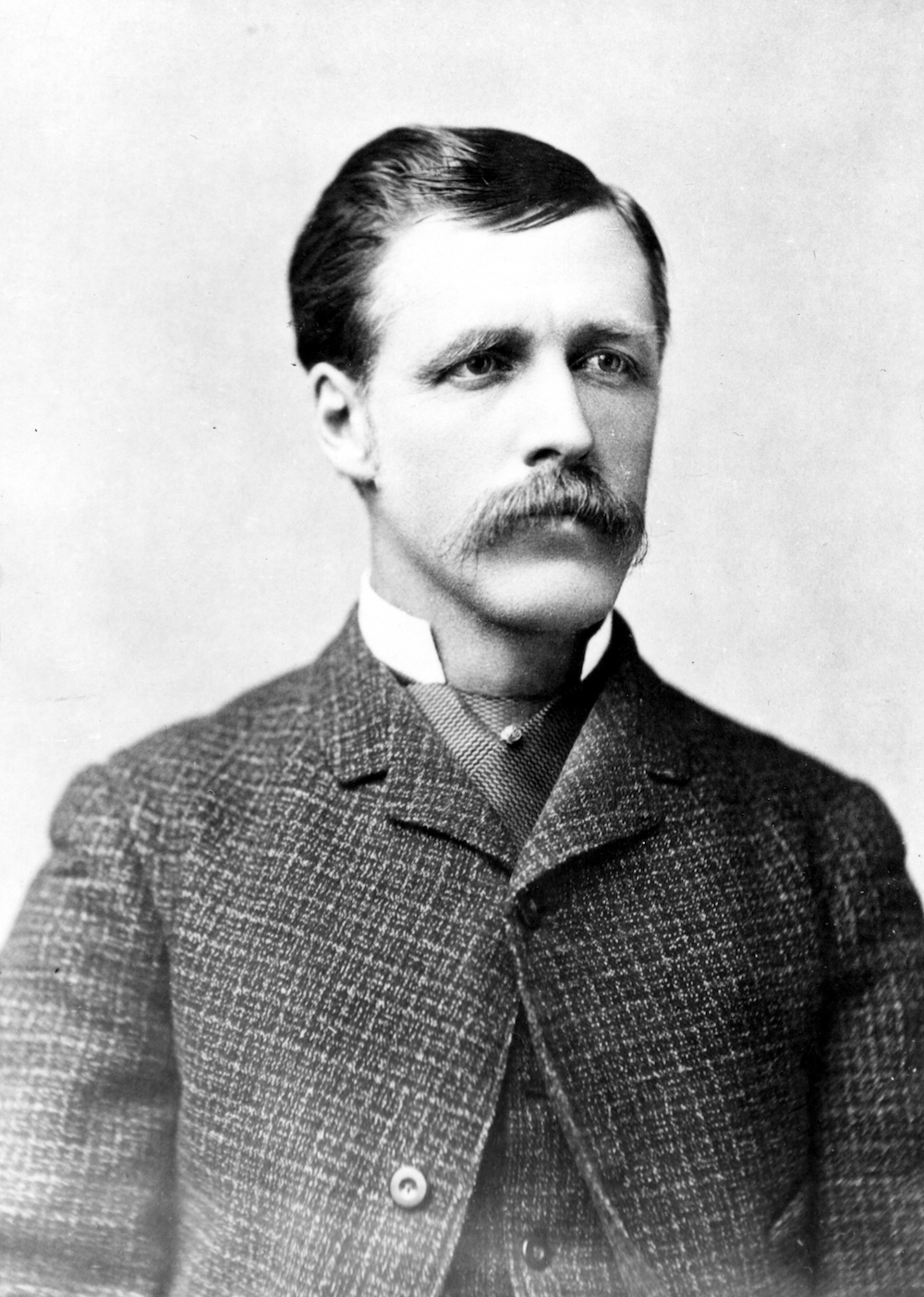

William Henry Jackson was more than a daring explorer scrambling around precipices, climbing fourteen thousand foot peaks and scaling sheer canyon walls. He was the finest of the nation’s wet-plate photographers. He perfected his craft on the job creating powerful photographs of unparralled beauty. The splendor of lofty mountain peaks, gaping canyons, spectacular waterfalls and wild rivers provided an amazing natural backdrop for this adventurous photographer.

Jackson was forced to develop his negatives on the spot, within thirty minutes of making an image under incredibly difficult situations. This required him to carry a portable darkroom, weighing as much as three hundred pounds, wherever he went. The mules hauling his equipment would, at times, fall destroying his work.

Jackson was born in Keeseville, New York in 1843, the oldest of seven children. His mother, a watercolorist taught him how to draw and paint. Jackson’s father experimented with photography and gave his son camera parts as toys.

Jackson learned the craft of photography working in portrait studios as a retouching artist in upstate New York and Vermont. After serving in the Union army in the Civil War as staff artist and mapmaker, he drifted from place to place working as a bushwhacker, a carpenter, a wrangler, a guard on wagon trains and an art tutor.

In 1868, he settled in Omaha, Nebraska launching his career as a landscape photographer. He was commissioned by the Union Pacific Railroad to take ten thousand views along the train’s route for advertising and promotional purposes.

These photographs caught the eye of Ferdinand V. Hayden, director of the U.S. Geological Survey of the Territories. In 1870, Hayden invited Jackson to join his expedition to Yellowstone for travel expenses, food, shelter and adventure. He would be part publicist, part documentarian. The photographs, along with the paintings of Thomas Moran, a guest artist, would be used to ply Congress for money for future expeditions while giving vicarious pleasure to the public. These detailed photographs and paintings were used by Hayden to help convince Congress to make Yellowstone the country’s and the world’s, first National Park in 1872.

In 1873, Hayden’s expedition shifted to the Colorado Territory. Jackson’s photographs depicted a land of expansive proportions. He roamed the West Elk mountains in the Crested Butte area photographing a stunning reflection of the three peaks, Ruby, Owen and Purple on Lake Brennand (Irwin), and created striking images of Teocalli, Gothic and Italian Mountains while passing through Brush Creek.

One of Jackson’s most famous photographs, The Mount of the Holy Cross was taken standing on a thirteen thousand foot peak on Notch Mountain after a frigid night.

In 1880, Jackson opened a studio in Denver working as a commercial photographer. He was sought after by the railroads for his trademark views. He traveled the world photographing railroads, scenery and people. On his return home, he and his assistant, George Mellen joined the Detroit Photographic Company.

Jackson produced over eighty thousand photographs of the American West, working until the end of his life in 1942, at the age of ninety-nine. His photographs are an invaluable legacy to the nation and remain, to this day, immensely significant to the pictorial history of the expansion of the West.